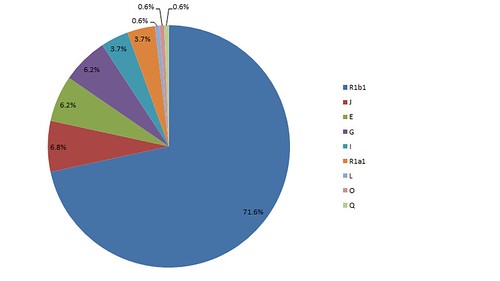

Growing up, I knew very little about my direct paternal ancestry. I first met my paternal great grandfather Weldon Earl Borland after the death of my grandfather John Earl Borland in 1986. After college, I began working on creating a family tree, beginning with information I obtained from interviewing Weldon. I have since continued compiling information regarding the history of the Borland family, and recently had my

Y chromosomal DNA tested. The following is the history of my paternal ancestral line, generation by generation:

Generation 1: Kevin Borland

I was born January 20, 1975, in Jersey City, New Jersey, to parents Steven Thomas and Kathleen (Szczesny) Borland. Shortly after my birth, my family moved to Morris County, New Jersey, where we lived for three years before relocating further northwest to Hardyston, Sussex County.

My childhood homes in Lake Hiawatha, Morris County (left) and Hardyston, Sussex County (right)

My childhood homes in Lake Hiawatha, Morris County (left) and Hardyston, Sussex County (right)

I currently reside in Arlington, Virginia, with my wife Thidawan and my stepson Jaras. I am an attorney by profession.

Kevin Borland family

Generation 2: Steven Thomas Borland

Kevin Borland family

Generation 2: Steven Thomas Borland

My father was born August 7, 1950, also in Jersey City, to parents John Earl and Helen Eloise (Freudenberg) Borland. He grew up in Jersey City, and remained in New Jersey until retiring to Florida about 10 years ago. Steven served in the United States Army, and was deployed to Germany during the Vietnam War. Upon his return to New Jersey, he worked for the United Parcel Service (UPS) most of his life, until he began suffering from leukemia. He died in Tampa June 15, 2010, from complications arising from a bone marrow transplant, after which he was buried in Leesville, Ohio, a few rows away from his father's grave.

Steven Thomas Borland's high school yearbook photo (left) and pictured with his two sons Kevin and Steven in Florida (right)

Generation 3: John Earl Borland

Steven Thomas Borland's high school yearbook photo (left) and pictured with his two sons Kevin and Steven in Florida (right)

Generation 3: John Earl Borland

John Earl Borland was born May 16, 1924, in the now-defunct village of New Hagerstown, Carroll County, Ohio, to parents Weldon Earl and Elizabeth Marie (Forbes) Borland. John's parents divorced prior to his birth, and John was raised by his mother Elizabeth on her parents' farm in New Hagerstown. John served in the United States Navy during World War II, after which he relocated to Jersey City, where he met his first wife, my grandmother Helen. John worked most of his adult life at the Ballentine Brewery in Newark, New Jersey. John and Helen eventually divorced, and John remarried to Geraldine (Winblad) Van Deusen. Upon John's retirement, he returned to Ohio with Geraldine, where he died of lung cancer, November 10, 1986.

John Borland's high school graduation photo (left) and pictured with wife Helen, stepson Michael and sons John and Steven (right)

Generations 4: Weldon Earl Borland

John Borland's high school graduation photo (left) and pictured with wife Helen, stepson Michael and sons John and Steven (right)

Generations 4: Weldon Earl Borland

Weldon Earl Borland was born July 3, 1906 in Bowerston, Harrison County, Ohio, to parents James Couthren and Lizzie Alberta (Miller) Borland. Weldon grew up in Bowerston, but as an adult relocated to Akron, Ohio, where he worked for Goodyear. After some time, he left Goodyear and started his own business called "Volume Sewing." Weldon and his employees manufactured a variety of sewn items ranging from army uniforms to boat covers. Weldon married briefly my great-grandmother Elizabeth Marie Forbes, and later Vivian Kniseley. My great-uncle Jeffrey James Borland is a son from Weldon's second marriage. Weldon died March 2, 2002, while he was hospitalized for treatment of pneumonia, and was buried in Long View Cemetery in Bowerston, as are both of his parents. He was 95 years old at the time of his death.

Weldon Borland in his youth (left) and later in life pictured with his long-time companion Rose Simmons (right)

Generation 5: James Crouthen Borland

Weldon Borland in his youth (left) and later in life pictured with his long-time companion Rose Simmons (right)

Generation 5: James Crouthen Borland

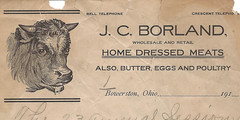

James Crouthen Borland was born September 25, 1877, also in Bowerston, to parents James II and Catherine Jane (Walker) Borland. He was the owner of "J.C. Borland Wholesale and Retail," a general store in Bowerston. James and wife Lizzie Alberta (Miller) Borland had four children, two of which survived to maturity, my great-grandfather Weldon, and his sister Ruth Eleanor Borland. James died April 19, 1943 in Bowerston, of a cerebral hemorrhage secondary to chronic alcoholism. At the time of James' death, he and Lizzie were divorced.

James Borland and family behind the counter at J.C. Borland Wholesale and Retail (left), and James' letterhead (right)

Generation 6: James Borland II

James Borland and family behind the counter at J.C. Borland Wholesale and Retail (left), and James' letterhead (right)

Generation 6: James Borland II

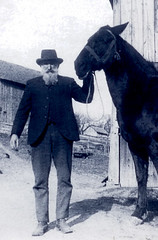

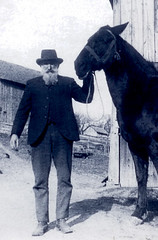

James Borland II was born October 2, 1835 in Orange Township, Carroll County, Ohio, probably in or near New Hagerstown. His parents were James and Mary (McQuiston) Borland. He married Catherine Jane Walker and they had two children, Charles Oliver Borland (1871-1931) and James Crouthen Borland (1877-1943). James was a farmer by occupation, and he served as a volunteer soldier in the United States Civil War. His Civil War rifle remains in the family. James died May 11, 1903 in Bowerston.

James Borland II with his horse (left), grave of James and Catherine Borland at Long View Cemetery (right)

Generation 7: James Borland

James Borland II with his horse (left), grave of James and Catherine Borland at Long View Cemetery (right)

Generation 7: James Borland

James Borland was born 1792 in or near Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, to parents Samuel and Lydia (Gregg) Borland. He married Mary McQuiston of Butler, Pennsylvania, with whom he fathered at least six children. A McQuiston family history states that James was a music teacher in his youth. Census data reveals that he was a farmer, later in life. James lived until at least 1850, although his grave has not been located. It is suspected that he may be buried in New Hagerstown.

Generation 8: Samuel Borland

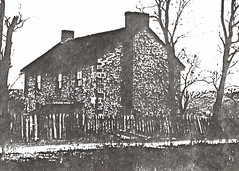

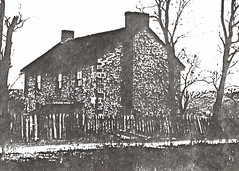

Samuel Borland was born 1748 in County Antrim, Northern Ireland, to parents John and Rachel Borland. After immigrating to the United States prior to 1783, he married Lydia Gregg in Pennsylvania and had 11 known children. Samuel and his family resided in Manor of Denmark, near Export, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, since at least 1800, where Samuel built the first stone house in the Manor Valley. Samuel died 1811, after which Lydia obtained a land patent in Carroll County, Ohio, where subsequent Borland generations settled. Samuel and Lydia are buried in Congruity, Salem Township, Westmoreland County. Lydia's suspected brother David Gregg was a great-grandfather of United States President Harry S Truman.

Samuel Borland residence in Manor of Denmark (left), Samuel and Lydia Borland graves (right)

Generation 9: John Borland

Samuel Borland residence in Manor of Denmark (left), Samuel and Lydia Borland graves (right)

Generation 9: John Borland

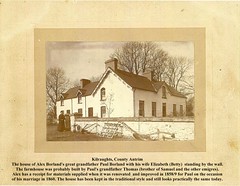

Based on the year of his first marriage (1738), John Borland must have been born prior to 1720. Based on the names of his children, his father was likely named James. John was the progenitor of the Borland family of the Kilraughts Parish in County Antrim. He first married a woman by the name of Ann in Lisburn, by whom he fathered four children. After Ann's death, prior to 1745, he remarried to a woman named Rachel, widow of a Mr. Moore, by whom he fathered an additional 9 children. While some of the children immigrated to the United States, others remained in and around Kilraughts. John was a farmer by occupation. He died around 1778 in or near Kilraughts. The location of John's birth is presently unknown, although one might speculate that since he first married in Lisburn, he was probably born somewhere in the vicinity of Belfast.

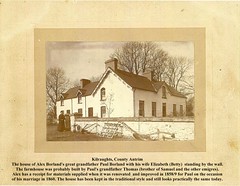

Borland residence in Kilraughts

Generation 10: James Borland

Borland residence in Kilraughts

Generation 10: James Borland

The name James is based on the fact that John Borland (of generation 9) named his first-born son James. The custom at the time, both in Scotland and Northern Ireland, was to name one's first-born son after the child's paternal grandfather. James would have been born circa 1685, probably in or near Belfast. In addition to his son John of Kilraughts, he also fatherd a son Andrew who resided in Ballymoney. My direct line of paternal ancestry can only be traced as far as this 10th generation using conventional genealogical methods, i.e. through the discovery and review of historic documents, gravestones, published family histories, etc.

Generations 11-12: Borlands of Belfast

The similarity between my Y-DNA and the Y-DNA of David Hunter Borland of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, suggests that the Borlands of Clondavaddog, County Donegal, descend from a very close relative of James Borland (of generation 10). Furthermore, based on the small number of Borland families in Ulster (the northernmost of Ireland's 4 provinces) enumerated in the 1796 list of Irish flax growers, clustered almost entirely near Clondavaddog and Ballymoney, it would appear that either James' father or grandfather was likely the immigrant ancestor of all of the early Borland families of Ulster, having come to Belfast from Scotland (Borland being a Scottish surname). According to the Wikipedia Article entitled "

History of Belfast," after the

Irish Rebellion of 1641, many Scots who had come to Ulster as part of the Scottish army sent to put down the rebellion, settled in Belfast after the

Irish Confederate Wars." A Borland ancestor of about the 12th generation would have been just the right age (having likely been born around the 1620s) to have been one of the Scottish soldiers.

Generations 13-15: Borlands of Strathclyde

According to Ancestry.com, my closest Y-DNA match (using 46 short tandem repeat markers) is to a Randy Scott Borland, who, like me, resides in Northern Virginia. Ancestry.com estimates that we are probably related within 15 generations. Although I have been thusfar unable to contact Randy, I independently constructed his family tree. Upon doing so, I learned that he descends from a line of Borlands that straddles the parishes of Galston and Loudoun, in the Strathclyde region of Scotland. His Borland line does not pass through Ireland. This suggests that that our distinct branches of the Borland family both descend from a common Borland ancestor who lived in the Strathclyde region of Scotland, possibly born around the 1530s (based on an average generation gap of 30 years). Unfortunately, the church records of Galston and Loudoun only go back to the 1680s, where in Loudoun, for example, in 1684 a child named Anna was baptized, with the name Archiblad Borland listed as her father.

Generations 16-18: Origin of the Borland Surname

In Ancestry.com's ranking of genetic separation of Y-DNA donors, once we reach STR matches estimated within approximately 19 generations, all matches have surnames other than Borland. This suggests that the Borland surname was adopted in my direct paternal line between generations 16 and 18. Again using an estimated average generation gap of 30 years, that brings us to the time period between the 1440s and 1500s. My first ancestor to have used the name Borland would have spoken an Anglic language, probably either Scots or Middle English (ancestral to the modern English language).

Generations 19-21: Beyond Borland and Beyond Scotland

STR matches estimated to converge with my paternal lineage at generations 19 and 21 carry the surnames Shaw and Fielder, respectively. Both of these surnames, like the name Borland, are of Anglic origin, suggesting that the Borlands, Shaws and Fielders, shared a common Anglic-speaking direct paternal ancestor born around 1350, who likely lived in England (since Shaw and Borland are Scottish names, whereas Fielder, a line which split off from my lineage earlier is of English origin). Interestingly, all three names are also topographic surnames. It would appear that the names Borland, Shaw and Fielder were adopted by three branches of the same family, prior to which (before generation 18) the family may not have employed the use of a surname. The migration from England to Scotland likely occurred around generation 20.

Generation 22: Brief Passing Through Cornwall

A 12/12 STR match, found on ySearch.org, with an individual bearing the surname Pennock suggests a 90% chance of a direct paternal relation within 23 generations. Pennock is a Cornish name, indicating that the Borland paternal ancestor born around 1320 may have lived in Cornwall, in southwestern England. Pennock, once again, is a topographic surname, deriving its name from Pignocshire (pronounced with a silent "g") in Cornwall.

Generation 23: From Gascony to England During the Hundred Years' War

Another 12/12 STR match from ySearch.org reveals a link within 23 generations to an individual with the surname "de Ayala" who has traced his paternal line back to Gascony, a historically Basque region in southwestern France. "De Ayala" is another topographic surname originating in Ayala, a village in Basque Country, Spain. This suggests that my 20x great-grandfather, born around the year 1290, lived among the Basque, in either northwestern Spain or southwestern France. I suspect he resided in Gascony, since that would explain the migration in the next generation or so to Cornwall. This has to do with the

Edwardian War being fought in Gascony from 1337-1360 (the first phase of the Hundred Years' War). At that time, Gascony was English territory. It would not be surprising if some citizens of Gascony may have moved to other, perhaps more peaceful, English territories during the war. Cornwall is the closest portion of present-day England to Gascony, geographically, perhaps making it an obvious choice for my ancestor, even if the trip was almost 700 miles by sea. If this theory is correct, than the name "de Ayala" may have been the surname used by my direct paternal ancestors prior to the adoption of an Anglic language. This would explain the various Anglic topographic surnames used by different branches of the family in later generations. Perhaps each branch of the family switched from "de Ayala" to a new Anglic topographic surname upon adoption of an Anglic language. This would also explain why the surname Borland seems to have arisen at a time long after surnames were being commonly used in Scotland.

Generations 24-28: Basque Country

A more distant STR match, estimated by Ancestry.com to converge with my paternal lineage at generation 28 (mid 12th century), further supports a Basque Country homeland of the paternal ancestors of the Borlands. At this level, the surname Zurita is added to the list of surnames sharing a common paternal origin. Zurita is an Aragonese surname, originating in northern Spain. Y-DNA STR analysis appears to indicate that my direct paternal line resided in the Pyrenees by the 13th century, where Navarro-Aragonese languages were spoken, in addition to Basque. Muslims would have been more likely to have spoken the Navarro-Aragonese languages, since they did not descend from the indigenous Basque people.

Generation 29: Salamanca to Basque Country

A 31/37 STR match in the Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation database with an individual with the topographic surname Bejar suggests my paternal ancestral line may have resided in or near Salamanca in the 29th generation. Béjar is the name of a town in Salamanca. The migration from Salamanca to the Basque Country in the Pyrenees was likely a result of the

Reconquista, a gradual process in the Middle Ages during which several Christian kingdoms succeeded in retaking the Muslim-controlled areas of the Iberian Peninsula broadly known as Al-Andalus. The paternal ancestors of the de Ayala/Borland family , were likely Muslims (Moors) who retreated to the mountains in northwestern Spain as a result of the Reconquista. (See below for evidence supporting this theory.) According to Wikipedia, "The main phase of the Reconquista was completed by 1249, after the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, when the sole remaining Muslim state in Iberia, the Emirate of Granada, became a vassal state of the Christian Crown of Castile." This fits very well into our generational timeline.

The animated map below, provided by the Norwegian historian Tolke, depicts the timeline of the Reconquista. The retracting green portion of the animation represents the portion of the Iberian Peninsula dominated by the Moors.

Generations 30-34: One Hundred Fifty More Years in Spain

Generations 30-34: One Hundred Fifty More Years in Spain

Continuing on through generation 34 (early 10th century), the surnames Salinero, Levario, Rodriguez and Bermudez appear among my STR matches, indicating the presence of my paternal line in Spain for over two centuries. Based on these patronymic and occupational surnames, however, a precise region in Spain cannot be identified.

Generations 35-40: Two More Centuries in Spain

Beyond 35 generations, STR comparison ceases to be a particularly useful method of tracing paternal migration, and we must turn to single-nucleotide polymorphism. While I have not personally taken a deep SNP y-dna haplogroup test, fortunately, my approximately 30th paternal cousin Armondo C. Rodriguez has. His results reveal that he, as well as the Borlands, are of y-DNA haplogroup E1b1b1b1b (M183), indicating recent North African ancestry. We then turn to the history of Spain, and discover that in the early 8th century (around generation 40 on our timeline), nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula was conquered (711–718) by largely Moorish Muslim armies from North Africa. The Moors referred to the conquered peninsula as Al-Andalus. My paternal 37x great-grandfather would have spoken Andalusian Arabic.

Map showing migration route from Northern Africa to Northern Ireland, as discussed thusfar, with nodes at A: Morocco, B: Salamanca, C: Basque Country, D: Gascony, E: Cornwall, F: Strathclyde and G: Ulster.

Generations 41-185: Over Four Thousand Years in the Maghreb

Map showing migration route from Northern Africa to Northern Ireland, as discussed thusfar, with nodes at A: Morocco, B: Salamanca, C: Basque Country, D: Gascony, E: Cornwall, F: Strathclyde and G: Ulster.

Generations 41-185: Over Four Thousand Years in the Maghreb

Y-DNA haplogroup E1b1b1b1b (M183) is believed to have emerged in the

Maghreb, or northwestern Africa, around 5,600 years ago, which would suggest that my paternal ancestors spent over 4,000 years living in the Sahara. M183 is sometimes referred to as the Berber marker, since in some groups of Berbers, nearly 100% of the population exhibit this mutation. The Moors who invaded Spain were largely of Berber ethnicity.

Generations 186-750: From the Nile to the Sahara

Haplogroup E1b1b (M215), ancestral to E1b1b1b1b (M183) is believed to have emerged in eastern Africa, around 22,400 years ago, perhaps along the Nile in present-day Ethiopia or Sudan. 750 generations ago, my direct paternal ancestor may have spoken an ancient language, ancestral to the modern Nilo-Saharan languages.

Generations 751-1200: From the Ethiopian Highlands

Haplogroup E1b1 (P2/PN2), ancestral to E1b1b (M215) is believed to have emerged in the Ethiopian highlands, around 35,000 years ago. 1200 generations ago, my direct paternal ancestor may have spoken a language not only ancestral to the Nilo-Saharan languages, but also to the Niger-Congo and Mande languages.