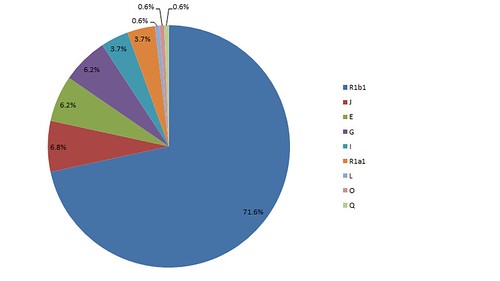

The above chart includes data from 162 male volunteers who submitted their Y-chromosomal DNA results to Family Tree DNA's Basque DNA project. Individuals who submitted their Y-DNA results claim to be of direct male Basque descent. Contributing volunteers included residents of Europe, Asia, and North and South America. Analysis of the data reveals that 71.6% of the participants in this study carry Y-DNA of haplogroup R1b1 and its subclades.

Basque People

The Basques as an ethnic group, primarily inhabit an area traditionally known as the Basque Country, a region that is located around the western end of the Pyrenees on the coast of the Bay of Biscay and straddles parts of north-central Spain and south-western France. Since the Basque language is unrelated to Indo-European, it is often thought that they represent the people or culture who occupied Europe before the spread of Indo-European languages there.

Y-DNA in the Field of Linguistics

Y-DNA haplogroup testing is a valuable tool in the study of historical linguistics. Y-DNA is carried from father to son, and mutates at a somewhat predictable rate. Haplogroups are clades of DNA types that share a distinct defining mutation or mutations. Each such mutation occurred in a single person at some point in the past. Since the person in which that mutation occurred necessarily spoke a language (at least in the time-frame of the past 50,000 years or so), and since a large percentage of children learn to speak the same native language as their father, one can use Y-DNA studies to track the historical evolution of languages, and uncover ancient relationships between living language families, to a surprising degree of accuracy.

When using Y-DNA as a tool to discover relationships between living language families, however, one must take into account the fact that there are several reasons why children may not learn to speak the native language of their fathers. The most obvious of such a situation is when the father either moves to a region that speaks a different language or has a child in a region where another language is dominant in addition to his native language (i.e., a more dominant local language is taught in schools, used in business, etc.), and rather than learning the native language of the father, children adopt the local language.

The goal in interpreting the data from this study is to determine which, if any, of the individuals whose Y-DNA first contained the defining mutations of the haplogroups, may have spoken a language ancestral to modern Basque, i.e. "Ancient Basque."

Haplogroup E Among Basque People

93.8% of those tested reported haplogroups of Eurasian origin, whereas 6.2% reported haplogroup E and its subclades. Haplogroup E is common among ethnic groups which originated along northern portions of the Nile River in Africa, including speakers of Nilo-Saharanm, Niger-Congo, Mande and certain Afro-Asiatic languages. The infusion of Y-DNA haplogroup E among the Basque population likely took place long after speakers of the ancestral Basque language arrived on the Iberian Peninsula, perhaps after the Afro-Asiatic speaking Moors invaded southern Europe. That is to say, the Basque language is unlikely to share a common origin with the Nilo-Saharan or Afro-Asiatic language families, although males of Northern African descent who migrated north to the Iberian Peninsula apparently interbred with women of the Basque population, perhaps influencing the local "Ancient Basque" language, but not replacing it.

Outliers in Haplogroups L, O and Q

Of the 162 individuals tested, there was one individual who carried haplogroup L, one who carried haplogroup O, and one who carried haplogroup Q. These haplogroups are of Eurasian origin, but are probably not associated with speakers of Ancient Basque. The individual who carried haplogroup Q resided in China and reported that his most distant known paternal ancestor resided in Mexico and had a Basque surname. It should be noted that Y-DNA haplogroup Q is the most common haplogroup among native (non-European) Mexicans, and not likely indicative of a Basque origin, despite the Basque surname. Haplogroups L and O generally correspond with South Asian and Asiatic languages, respectively. As the present-day Basque language shares little in common with members of these well-studied language families, the individuals likely represent a very small segment of the Basque population who descend from recent (less than 5000 years ago) immigrants to the Basque country from southern and eastern Asia.

Haplogroup R1a1 on the Iberian Peninsula

While haplogroup R1a1 appears in this sample at a percentage of 3.7%, that rate is similar to, if not less than, the occurrence of R1a1 in surrounding regions. R1a1 likely corresponds to DNA of native speakers of Indo-European languages, who settled the Iberian Peninsula and likely wiped out all recent branches of the Ancient Basque language with the exception of the languages of the Basque country. Haplogroup R1a1 is found in all locations where Indo-European languages are spoken, and the person in which its defining mutation occurred likely spoke a language ancestral to Indo-European, not to Basque.

Northwest Caucasian Haplogroup G

Y-DNA haplogroup G has not been definitively associated with any living language family, although it is common among speakers of Northwest Caucasian languages. The language of the progenitor of haplogroup G may only be manifested in the Northwest Caucasian substrate which differentiates the Northwest from the Northeast Caucasian languages. Since there are unlikely any modern surviving languages that descend directly from the language spoken by the progenitor of haplogroup G, it is difficult to rule out the haplogroup as corresponding to an Ancient Basque precursor. However, due to the overwhelming majority of haplogroup R1b1 (which shares the same lack of known modern surviving descendant languages) among the Basque population, it seems logical that many carriers of haplogroup G may have spoken a Vasconian (pre-Basque) language (perhaps since as long as 10,000 years ago), after native Vasconian speaking carriers of R1b1 dominated their native culture, perhaps shortly after the last ice age.

Cro-Magnon Haplogroup IJ

10.5% of the sample reported haplogroups of either I or J, both haplogroups that represent subsequent mutations from an earlier Cro-Magnon haplogroup IJ, which appears to have originated in the Caucasus. This is a large percentage of the sample that cannot be discounted. The progenitor of haplogroup J may have spoken a language ancestral to the Northeast Caucasian and Kartvelian language families. The progenitor of haplogroup I spoke a language belonging to an extinct family that may only have modern observable manifestation in the substrate of vocabulary found in the Germanic languages (approximately 1/3 of the lexicon) that is not traceable to Proto-Indo-European origin. While neither haplogroups I nor J can be definitively ruled out as corresponding to the Basque language, it appears that the Basque language does not share much in common with the Northeast Caucasian or Kartvelian languages, nor have I found any source that suggesting that its lexicon overlap the Proto-Germanic substrate.

Vasconian Haplogroup R1b1

Based on the data from this study in a vacuum, it seems very likely that if the progenitors of any of these haplogroups spoke a Vasconian language, it should be R1b1, as R1b1 accounts for 71.6% of the sample population. However, looking outside this study, R1b1 is equally common among most Indo-European speaking (Spanish and Portuguese, e.g.) populations of the Iberian peninsula, and almost as common in regions to the east where other Romance languages are spoken such as French and Italian. Perhaps remnants of the language spoken by the progenitor of R1b1 can be found by studying the differences between the Romance (Italic) brancih of the Indo-European languages from other Indo-European subfamilies. I suspect some of the differences may be accounted for by a Vasconian substrate that represents linguistic elements of other languages descended from Vasconian that may have been spoken by populations who assimilated into the western Indo-European culture, and adpoted Indo-European as their language. I believe this hypothesis is more sound than a IJ origin of the Basque language, based on geographic data on the present location of haplogroup R1b1 vs. haplogroups I and J. For example, haplogroup I is distributed widely in Scandinavia and in regions where Germanic languages are spoken. It seems likely that if there was a living descendant language of the language spoken by the progenitor of haplogroup I, it would have the highest likelihood of surviving in Germanic speaking Europe, not in the Pyrenees Mountains where R1b1 y-DNA is dominant among Italic speakers who (if they inherited their language from their ancestors rather than by assimilation) would be expected to have R1a1 Indo-European DNA.

Basque Language Isolate

One might ask, if the Basque language is associated with R1b1, and the Indo-European languages are associated with R1a1, (both clades of R1), why is the modern Basque language so different from all of its closest genetic relatives? However, consider, for example, the incredible difference between the English and Hindi languages (both Indo-European) which probably only diverged from their most common ancestor about 5,000 years ago. If not for available linguistic data from the numerous other languages in the Indo-European family, one might be highly skeptical about their common origin, especially due to the geographic distance where the two languages are spoken, and the differences in culture, appearance, religions, etc., between the populations by whom they are spoken. One must keep in mind that R1a and R1b diverged from their common y-DNA ancestor R1 approximately 18,000 years ago, and there are no intermediate languages on the R1b side that survived to modern times, with the possible exception of Basque. It should not be surprising that Basque seems completely foreign to the Indo-European languages, in this context.

Furthermore, even if the progenitor of R1a spoke an ancient Indo-European language and the progenitor of R1b spoke an ancient Vasconian language, that does not necessarily imply that the two ancient languages were closely related. The progenitor of R1 (ancestral to R1a and R1b) probably lived in Siberia some 25,000 to 30,000 years ago, approximately 10,000 years prior to the mutations that occurred that created the subclades of R1a and R1b. In those 10,000 years, the descendants of the progenitor of R1 may have come to speak many languages unrelated to the the native language of their ancestor by means of assimilation as they migrated across Asia. That is to say, while R1a and R1b carriers are undoubtedly genetically related, an inter-disciplinary approach including efforts by experts in the fields of anthropology, archaeology, linguistics, genetics, philology and other sciences, is required to prove or disprove any ancient relation between the Basque language and the Indo-European languages. Also, an examination of the Burushoski language spoken by (among others) descendants of R1's closest relative R2 may provide some evidence helpful to determining the origin of the Basque language. Unfortunately, Burushoski, spoken in portions of present-day Pakistan, is also a language isolate.

Related Reading

For what they were... we are: Linguistic musings: Basque and Proto-Indoeuropean

Diagram, research and analysis by Kevin Borland. Data provided by Family Tree DNA. Text of subsection "Basque People" derived from Wikipedia.

1 comment:

You make various mistakes that do no allow you and so many other linguists to find answers. Those mistakes have to do with the incorregible romantic view of the basques:

1) At the time of the roman invasuion what today is the basque country was reported to be inhabited by celts (varduli and caristii), and various geographical featuresd there had , and still some have, celtic toponimics. The basques were living in todays Navarre, part of Rioja and Aragon. The Ebro valley was multilingual. Today basque country is the product of political and historical arrangements and not a unitary ethnic people from the prehistory.

2) You believe that language is transmited by men with a particualr DNA. It is more likely that the R1b that you talk about came to the basque country with the early protoceltic invasions and that these people exterminated or enslaved most of the males. The basque language continued to be spoken in isolated villages in the Piririnees and above all survived thanks to the women in the homes. At the fall of the Roman empire the use of basque expanded and by the way it continued in north Aragon till well into the middle ages.

3) Basque was not the only pre-european language spoken in Spain when the romans came. Iberian languages were spoken in the eastern Pirinees, the Ebro valley and the mediterranean coast, even in western Andalousia. The iberian languages had sone yet not clear relation with basque. early toponimics as far as Granada (Iliberri) sounded basque/iberian.

Cease to romantify basques. Preindoeuropean languages besides basque were spoken in many parts of Spain, who was in many areas multilingual and languages which survive may not be the ones of the dominant males but those learnt in the home. If the R1b was a pre-indoeuropean haploid how comes that it is as frequent amongst irish weslhmen and the bashkires of Perm as fequent or more than in the basque country. And in North Aragon, where I come from, I2 haploid is around 20%.

Post a Comment